Pediatric Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Involving Staphylococcal Scarlet Fever

Sadie M Henry, Mark M Stanfield and Harlan F Dorey

Sadie M Henry1*, Mark M Stanfield2 and Harlan F Dorey1

1Military Readiness Clinic, Naval Health Clinic Patuxent River, USA

2Naval Office, Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Henry SM

Military Readiness Clinic

Naval Health Clinic Patuxent River, USA

Tel: + +1 301-342-1419

E-mail: sadie.m.henry.mil@mail.mil

Received Date: November 28, 2018; Accepted Date: January 18, 2019; Published Date: January 21, 2019

Citation: Henry SM, Stanfield MM, Dorey HF (2019) Pediatric Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Involving Staphylococcal Scarlet Fever. Med Case Rep Vol. 5 No.1:88.

Abstract

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis (AGEP) is a rare skin disorder that affects all ages. It is typically noted by an extensive rash, swelling, and erythema, with numerous white pustules. We present a case of a six-yearold who suffered from staphylococcal scarlet fever for several days, which progressed to AGEP, and illustrate the course of her in-patient and primary care.

Keywords

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis (AGEP); Pustules; Cutaneous reactions; Bacterial exanthema; Rash; Staphylococcal Scarlet Fever; Dermatology

Abbreviations

AGEP: Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis, ANC: Absolute Neutrophil Count, ED: Emergency Department, LAD: Lymphadenopathy, MRSA: Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus, SJS/TEN: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis, SSF: Streptococcal Scarlet Fever, SSSS: Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome, TSS: Toxic Shock Syndrome, VGE: Viral Gastroenteritis.

Introduction

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a cutaneous adverse reaction of very short onset characterized by an eruption of diffuse, non-follicular, sterile pustules covering an erythematous base. It is very rare, with approximately one to five cases per million per year across all ages, and is usually accompanied by fever, leukocytosis, and occasional mucous membrane involvement [1,2]. 90% of cases are caused by drug reactions, but there are reports of infectious etiology for AGEP [3-8]. Most pediatric exanthems arise from viruses; however a few stem from bacteria [9].

This report is based on one such uncommon pediatric pathology, having presented atypically from staphylococcal scarlet fever. There are examples of bacterial infection worsening to AGEP and specifically staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) developing into AGEP; similar to the progression we now report [10-12]. A milder form of SSSS, staphylococcal scarlet fever, is characterized by scarlatiniform rash and desquamation, yet lacks the strawberry tongue and pharyngeal infection of its streptococcal counterpart [13]. Many AGEP cases are iatrogenic in nature, but the novelty of the infectious nature in this case presents valuable insight to primary care/general practice, dermatology, and other specialties. We propose a mechanism by which acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis may be facilitated by staphylococcal scarlet fever.

Case Presentation and Assessment

A previously healthy six-year-old female presented with a confluent, macular, erythematous rash and a fever of 101°F/ 38°C for two days. The rashes started on her scalp and face one evening, and spread to the neck, chest, and axilla overnight. There was swelling in her face the next morning. With no obvious dietary or environmental triggers, toxic shock syndrome (TSS) was not suspected, though the patient was quite uncomfortable with pruritis. Past medical history, family/ social history, and review of systems was otherwise negative.

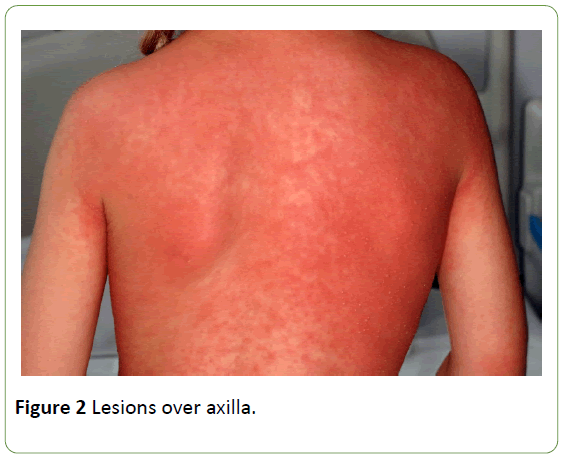

She began a course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, following suspicion of MRSA, and was given acetaminophen and diphenhydramine in the emergency department (ED) with follow-up scheduled in primary care. She was seen two days later in a pediatric clinic, at which time the pustules had spread to the abdomen, arms, and lower extremities, consistent with normal progression of AGEP [3,14-16]. She was admitted for further evaluation of her severe rash, with concerns for significantly worsening discomfort from pruritus. Dermatology was consulted, her pustules and nares were cultured, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was discontinued, and she was given triamcinolone 1% topical steroid. Ophthalmology was consulted to rule out ocular pathology; however nothing of note was found (Figures 1 and 2).

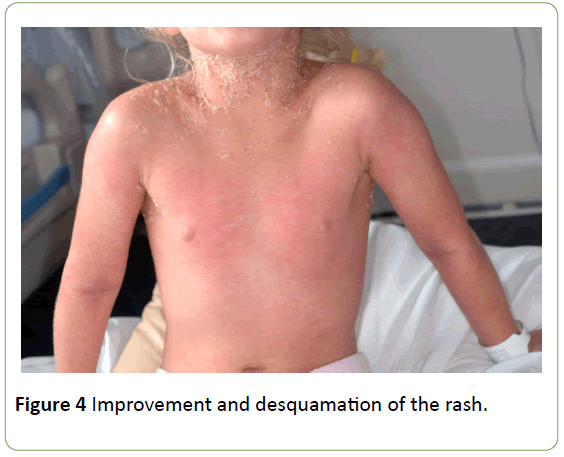

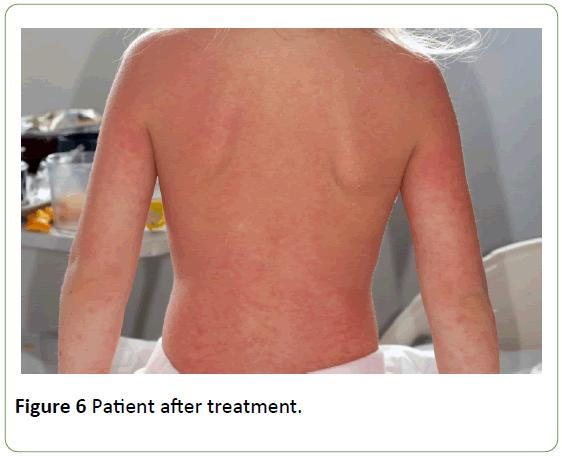

Lab cultures from a nasal swab showed a heavy growth of coagulase-positive Staphylococcus aureus which was pan-sensitive to antibiotics. She was discharged the next day, sent home with triamcinolone acetonide cream to be applied over her entire body, and mupirocin for the nares. Itching was controlled with diphenhydramine. The day after discharge, the patient showed much improvement and desquamation of the rash. A combination of clinical and pathological findings confirmed the definitive diagnosis of AGEP secondary to staphylococcal scarlet fever. Ongoing home care included mupirocin TID to the nares, Triamcinolone acetonide topical ointment TID to the body, and pimecrolimus ointment BID to the face (Figures 3-6).

Of note, five weeks later, she became ill again with a fever of unknown origin and lymphadenopathy (LAD) in setting of positive sick contact with a family member suffering from viral gastroenteritis (VGE). CBC at the time showed neutropenia with absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 900 and right submandibular LAD, consistent with a reactive LAD. Neutropenia is clinically relevant, given that AGEP is a neutrophilic event, and elimination of granulocytes after an infection, combined with antibiotic use, can result in neutropenia [15-17]. This patient improved without any further intervention over the next month.

Histopathology

Laboratory analysis usually yields spongiform pustules rich in neutrophils and other infiltrate such as eosinophils and necrotic keratinocytes [18,19]. Despite these values however, children are often treated clinically and without invasive sampling, as punch biopsies are avoided in children when possible. If blood testing is sought, neutrophil count indicative of AGEP typically exceeds 7.0 x 109/L [3].

Physical characteristics

AGEP occurs rapidly (≤ 1 day), with many nonfollicular, sterile, pinhead-sized pustules on a background of edematous erythema with flexural accentuation [3]. It generally starts on the face and spreads cephalocaudally [20]. Severe cases of AGEP may have coalescent pustules that result in erosions and may present similar to Stevens - Johnson syndrome/ toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) [21].

Diagnosis

Biopsies are helpful, but rapid onset, presentation, and strong clinical suspicion in conjunction with laboratory findings are keys to proper diagnosis. Though not used at the time of this patient’s care, we appreciate the scoring system provided by the European Study of Severe Cutaneous Reactions (EuroSCAR) study group in evaluating AGEP [16]. Table 1 illustrates the clinical and pathological factors relevant to this patient’s history and Table 2 lists pertinent laboratory values.

| Clinical criterion or variable | Patient attributes |

|---|---|

| Presentation in clinic | |

| Polymorphous, pin-sized pustules | Present |

| Erythema | Present |

| Distribution (e.g. intertriginous areas) | Fully consistent |

| Course | |

| Acute onset (≤ 1 day) | Yes |

| Fever of at least 38°C | Yes |

| Mucous membrane involvement | Slight |

| Rapid resolution | Yes |

| Histology | |

| Intra or subcorneal spongiform pustules | Present |

| Superficial, interstitial, and mid-dermal infiltrate rich in neutrophils > 7.0 × 109/L | Not tested at time of staph infection |

| Eosinophils in pustules | Yes |

| Necrotic keratinocytes | Yes |

| Gram stain | Negative for bacteria |

Table 1: Summary of findings.

| CBC w/ differential | Units | Ref Rng |

|---|---|---|

| WBC | 2.5 (L) × 103/mcL | (5.0-15.5) |

| RBC | 4.76 × 106/mcL | (4.2-5.4) |

| Hemoglobin | 12.0 g/dL | (12.0-16.0) |

| Hematocrit | 0.374 | (37.0-47.0) |

| MCV | 78.5 (L)fL | (81.0-99.0) |

| MCH | 25.2 (L)pg | (27.0-31.0) |

| MCHC | 32.2 g/dL | (31.0-36.0) |

| RDW CV | 0.118 | (11.5-14.5) |

| MPV | 8.8 fL | (6-12.5) |

| Platelets | 128 (L) × 103/mcL | (130-400) |

| Neutrophils | 41.5 (L)% | (50-70) |

| Lymphocytes | 46.7 (H)% | (20-40) |

| Monocytes (%) | 10.9 (H)% | (2-8) |

| Eosinophils | 0 | (0-5) |

| Basophils | 0.009 | (0-1) |

| ABS Neutrophils | 1.0 (L) × 103/mcL | (1.8-7.7) |

| ABS Lymphocytes | 1.2 × 103/mcL | (1.0-4.0) |

| ABS Monocytes | 0.3 × 103/mcL | (0-0.8) |

| ABS Eosinophils | 0.01 × 103/mcL | (0-0.5) |

| ABS Basophils | 0.01 × 103/mcL | (0-0.2) |

Table 2: Lab results five weeks after original diagnosis, showing neutropenia

Differential diagnosis

Alternatives to consider include: generalized acute pustular psoriasis, SJS/TEN, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), subcorneal pustular dermatosis, bullous impetigo, subcorneal IgA dermatosis, and generalized pustular psoriasis [3], pustular eruptions (caused by bacteria, funguses, herpes viridae, and the varicella zoster virus), SSSS [16], streptococcal scarlet fever, and pustulosis acuta generalisata. Timing and physical features during the course of the ailment is key to diagnosing correctly.

Treatment and Prognosis

Cases generally resolve on their own one to two weeks after discontinuation of an offending drug or resolution of an underlying illness. With the exception of extremely rare systemic involvement [17], it is limited to the skin and heals without scarring, although the desquamation can be alarming to patients, thus reassurance may be necessary, in addition to keeping the skin clean and the patient well hydrated to avoid complications [20]. During the pustular phase, consider moist dressings and antiseptics; during the desquamation phase, consider emollients. Treat pruritus as needed with topical steroids or other anti-pruritic creams (e.g. camphor/menthol topical ointment). Avoid oral steroids, as these exanthems are not long-lasting, and oral routes have not been shown to shorten the overall duration of the condition or improve outcomes [22]. If a drug reaction is suspected, consider patch testing for confirmation, which is much preferred to punch biopsy in children.

Discussion and Conclusion

This young girl had an unusual presentation of a rare condition. Although it is most commonly an adverse drug reaction in adults, it is important to consider acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis when examining cutaneous pathology in acutely-ill pediatric patients. Viral and bacterial exanthems are far less frequently encountered and may escape initial investigation.

Treating with oral antibiotics have not been shown improve the condition, and side effects from antibiotic treatment may be worse than the condition itself. Topical antibiotics are an excellent alternative in a non-toxic pediatric patient, but for deteriorating patients who may have disseminated staphylococcus or streptococcus infection, early treatment with IV antibiotics such as bactericidal clindamycin can be lifesaving. While AGEP is not associated with high rates of mortality, it is important to control in young, elderly, or pregnant patients, in addition to those that may be immune-compromised, such as certain surgical and/or admitted patients, or those with existing infection.

References

- Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, Halevy S, Bavinck JB, et al. (2007) Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—results of a multinational case–control study (EuroSCAR). Br J Dematol 157: 989-996.

- Liquete E, Ali S, Kammo R, Ali M, Alali F, et al. (2012) Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by erlotinib (Tarceva) with superimposed Staphylococcus aureus skin infection in a pancreatic cancer patient: A case report. Case Rep Oncol 5: 253-259.

- Roujeau JC, Bioulac-Sage P, Bourseau C, Guillaume JC, Bernard P, et al. (1991) Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: analysis of 63 cases. Arch Dermatol 127: 1333-1338.

- Sampson MM, Klinkova O, Vitko J, Casanas B (2018) A plethora of pustules: Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Am J Med 131: 639-641.

- Birnie AJ, Litlewood SM (2008) Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis does not always have a drug‐related cause. Br J Dermatol 159 :492-493.

- Rouchouse B, Bonnefoy M, Pallot B, Jacquelin L, Dimoux-Dime G, et al. (1986) Acute generalized exanthematous pustular dermatitis and viral infection. Dermatologica 173: 180-184.

- Naides SJ, Piette W, Veach LA, Argenyi Z (1988) Human parvovirus B19-induced vesiculopustular skin eruption. Am J Med 84: 968-972.

- Feio AB, Apetato MA, Costa MM, Sá JO, Alcantâra JO (1997) Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to Coxsackie B4 virus. Acta Med Port 10: 487-491.

- Bryant PA, Sharland M (2009) Acute childhood exanthems. Medicine 37: 686-690.

- Manzano S, Guggisberg D, Hammann C, Laubscher B (2006) Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: first case associated with a Chlamydia pneumoniae infection. Case Rep Dermatol 13: 1230-1232.

- Klein N, Hartmann M, Helmbold P, Enk A (2009) Akute generalisierte exanthematische Pustulose bei rezidivierendem HarnwegsinfektAcute generalized exanthematous pustulosis associated with recurrent urinary tract infections. Der Hautarzt 60: 226-228.

- Chu TW, Wang SH, Chi CC, Hsiao CH, Su LH (2014) Coexisting staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Dermatol Sin 32: 113-114.

- Weber DJ, Cohen MS, Rutala WA (2014) The acutely ill patient with fever and rash. InMandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases Updated Edition. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:chap 57.

- Turrentine JE, Dharamsi JW, Miedler JD, Pandya AG (2011) Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) caused by telavancin. J Am Acad Dermatol 65: e100-e101.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA (2015) Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol 73: 843-848.

- Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, Vaillant L, Roujeau JC (2001) Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)–A clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol 28: 113-119.

- Hotz C, Valeyrie‐Allanore L, Haddad C, Bouvresse S, Ortonne N, et al. (2013) Systemic involvement of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a retrospective study on 58 patients. Br J Dermatol 169: 1223-1232.

- Halevy S, Kardaun SH, Davidovici B, Wechsler J (2010) EuroSCAR: RegiSCAR Study Group: The spectrum of histopathological features in acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a study of 102 cases. Br J Dermatol 163: 1245-1252.

- Kardaun SH, Kuiper H, Fidler V, Jonkman MF (2010) The histopathological spectrum of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) and its differentiation from generalized pustular psoriasis. J Cutan Pathol 37: 1220-1229.

- Speeckaert MM, Speeckaert R, Lambert J, Brochez L (2010) Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: an overview of the clinical, immunological and diagnostic concepts. Eur J Dermatol 20: 425-433.

- Peermohamed S, Haber RM (2011) Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis simulating toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 147: 697-701.

- Alniemi DT, Wetter DA, Bridges AG, El‐Azhary RA, Davis MD, et al. (2017) Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: Clinical characteristics, etiologic associations, treatments, and outcomes in a series of 28 patients at Mayo Clinic, 1996–2013. Int J Dermatol 56: 405-414.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences