Ectopic Pregnancy of the Tubal Stump in ART Patients, Two Case Reports and a Review of the Literature

Piccioni MG, Riganelli L, Donfrancesco C, Savone D, Caccetta J, Merlino L, Mariani M, Vena F and Aragona C

DOI10.21767/2471-8041.100067

Piccioni MG1, Riganelli L1*, Donfrancesco C2,3, Savone D1, Caccetta J1, Merlino L1, Mariani M1, Vena F1 and Aragona C1

1Department of Gynecologic-Obstetrical and Urologic Sciences, University of Rome “Sapienza”, Rome, Italy

2Department of Feto-Maternal Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Portogruaro Hospital, Venice, Italy

3Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Rome “Sapienza”, Rome, Italy

- *Corresponding Author:

- Riganelli Lucia, MD

Department of Gynecologic-Obstetrical and Urologic Sciences

University of Rome “Sapienza”

Umberto I Policlinico of Rome

Viale del Policlinico 155, 00161 Rome, Italy

Tel: +39 3928994062

E-mail: lu.riganelli@gmail.com

Received date: September 24, 2017; Accepted date: September 29, 2017; Published date: September 30, 2017

Citation: Piccioni MG, Riganelli L, Donfrancesco C, Savone D, Caccetta J, et al. (2017) Ectopic Pregnancy of The Tubal Stump in ART Patients, Two Case Reports and A Review of The Literature. Med Case Rep Vol.3 No.3:32. doi:10.21767/2471-8041.100067

Copyright: © 2017 Piccioni MG, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: An ectopic pregnancy (EP) is the development of an embryo outside of the uterus. A heterotopic pregnancy (HP) is a multiple pregnancy with different sites of implantation, where one is intrauterine. These conditions have arisen also by the use of assisted reproduction techniques (ART), in addition to other causes.

Case presentation: We consider two cases of interstitial gestation in patients with previous omolateral salpingectomy for ectopic pregnancies, and a review of the literature. The correct diagnosis was achieved for both patients by the use of ultrasound transvaginal examination.

The first patient received a treatment of methotrexate (MTX) before performing a successful removal of the tubal stump, while the second one was managed directly with surgery.No postoperative complications occurred and they were discharged on the second day, postoperatively.

Conclusion: In women with first trimester pregnancy and a reported surgical history of a previous salpingectomy, transvaginal ultrasound examination should be performed in order to correctly and promptly identify the implantation site. When a salpingectomy becomes necessary, its complete resection should be performed, in order to prevent or significantly lower an EP occurrence in the tubal stump.

Keywords

Ectopic pregnancy (EP); Assisted reproductive technologies (ART); Tubal stump; Methotrexate (MTX); In vitro fertilization (IVF)

Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy represents a potentially serious medical and surgical condition for women during the reproductive age, with the possibility to evolve in an emergency obstetrical situation caused by the rupture and internal bleeding leading to hypovolemic shock and maternal death during the first trimester of gestation [1,2]. Its reported incidence is around 1.3% to 2% of natural pregnancies [3] and around 1.7% for pregnancies occurring with assisted reproductive technologies (ART), following a recent review performed in the USA [2], and a documented 2.5 to 5-fold increased risk toward spontaneously conceived pregnancies [4]. Today the increased incidence of pelvic inflammatory diseases and the higher request to perform ART represents amplification risk factors.

The vast majority of ectopic pregnancies (90%) implant occur in the tubal ampulla, while 2.5% of cases are identified in the tubal interstitial portion. In the vast majority of the cases the embryo prematurely implants itself in the fallopian tube before arriving in the uterine cavity. Only in approximately 2% of the cases EP occur in different regions: cornual, cervical, broad ligament, ovarian, and abdominal. An atypical and insidious severe event is that in which the embryo migrates from the uterine cavity to the contralateral tube [5]. The exceptional anatomic position into the tubal stump can result in a delayed identification of EP, increasing the risk of uterine rupture that soars after the 12th week of pregnancy.

Also, a heterotopic pregnancy (HP) is the result of the increased use of ART. HP is a multiple pregnancy with different site of implantation of embryos: one intrauterine, while the other(s) outside [6]. Infact HP is quite rare among the general population (1/7,963-1/30,000) [7], while its incidence in ART pregnancies vary between 1/100 to 1/3,600 [8].

In this case report we illustrate two rare clinical cases of interstitial EP occurring into the proximal tubal stump in women subjected to monolateral salpingectomy for a history of ectopic pregnancy. All procedures performed are in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Approval and informed consent have been obtained from each patient. The Institutional Review Board approved this study protocol.

We present also a systematic revision of interstitial pregnancies that occurred in tubal stump Table 1 and a review about EP in unusual sites in women having had previous salpingectomies Table 2.

| Author | Year | Age | Gravity and parity | Previous operation history | Mode of conception |

Gestation, weeks | Management | Internal Bleeding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corti [9] | 1964 | - | G3, P2 | Appendicectomy, left salpingo-oophorectomy for a serous ovarian cyst | Spontaneous | 5+3 d | Subtotal hysterectomy | 50 ml |

| Benzi [10] | 1967 | 27 | G2, P0 | Righ salpingo-oophorectomy for ectopic pregnancy | Spontaneous | 5 | Laparotomic excision of right tubal stump | Poor |

| Krzaniak [11] | 1968 | 30 | G2, P2 | Appendicectomy, Ovarian cystectomy |

Spontaneous | 9 | Laparotomic excision of left tubal stump | None |

| Bernardini [12] | 1998 | 36 | G4, P0 | Appendicectomy, Left salpingo-oophorectomy for interstitial tubal pregnancy |

Spontaneous | 4+5 d | A single i.m. dose of MTX (100 mg) on day 61 of gestation | NA |

| Sills [13] | 2002 | 39 | G0, P0 | Laparoscopic right salpingectomy for hydrosalpinx | IVF-ET (heterotopic pregnancy) | 6+4 d | Laparotomic excision of right tubal stump | 150 mL |

| - | - | 36 | G1, P1 | Laparotomic right salpingo-oophorectomy for an ovarian dermoid cyst | Spontaneous | 8 | Laparoscopic excision of right tubal stump | 20 mL |

| 27 | G3, P2 | Laparoscopic right salpingo-oophorectomy for ruptured ovarian pregnancy | Spontaneous | 6 | Laparoscopic excision of right tubal stump | 100 mL | ||

| Milingos [14] | 2008 | 38 | G6, P3 | Laparoscopic right salpingectomy and laparoscopic excision of the right tubal stump | Spontaneous | 5+6 d | Laparotomic excision of right tubal stump and left salpingectomy | NA |

| Faleyimu [15] | 2008 | 22 | G2, P0 | Left corneal resection for tubal pregnancy | Spontaneous | 5 | Laparotomic left salpingo-oophorectomy | 600 mL |

| Muppala [16] | 2009 | 38 | G3, P1 | Right salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy | Spontaneous | 6 | Laparoscopic cauterisation of right bleeding tubal stump | 500 mL |

| Pluchino [17] | 2009 | 34 | G1, P0 | Left salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy | Spontaneous | 7 | Laparoscopic excision of left tubal stump | 1500 mL |

| Sturlese [18] | 2009 | 30 | G1, P0 | Left salpingo-oophorectomy for an ovarian dermoid cyst | Spontaneous | 6 | Laparoscopic excision of left tubal stump | NA |

| - | - | 30 | G2, P0 | Laparoscopic right salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy | Ovulation induction | 8 | Laparoscopic excision of right tubal stump | 500 mL |

| 40 | G7, P4 | Laparoscopic right salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy | Ovulation induction | 6 | Laparoscopic excision of right tubal stump | 550 mL | ||

| 32 | G4, P0 | Laparoscopic left salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy | IVF-ET | 8 | Laparoscopic excision of left tubal stump | 700 mL | ||

| 30 | G3, P0 | Laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy for right ovarian pregnancy and left tubal pregnancy after ICSI | ICSI-ET | 7 | Laparotomic excision of tubal stump | 2000 mL | ||

| 42 | G3, P1 | Laparoscopic left salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy after IUI | IVF-ET | 7 | Laparoscopic excision of left tubal stump | 20 mL | ||

| 32 | G4, P0 | Laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy for bilateral hydrosalpinx | ICSI-ET | 6 | Laparoscopic excision of tubal stump | 200 mL | ||

| - | - | 33 | G4, P0 | Appendicectomy, laparoscopic partial left salpingectomy, laparoscopic total right salpingectomy | IVF-ET | 7+1 d | Laparoscopic excision of left tubal stump (salpingectomy with cornuostomy). | 100 mL |

| 37 | G0, P0 | Laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy for bilateral hydrosalpinx | IVF-ET | 6+2 d | Laparoscopic excision of right tubal stump | Large amount of free fluid and blood clots | ||

| Shavit [19] | 2013 | 35 | G0, P0 | Laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy for bilateral hydrosalpinx | IVF-ET | 6 | Laparoscopic excision of right tubal stump | Large amount of blood in the pouch of Douglas |

| Drakopoulos [20] | 2014 | 33 | G11, P3 | Laparoscopic tubal sterilisation by partial bilateral segmental isthmic salpingectomy | Spontaneous | 4+4 d | Laparoscopic excision of right tubal stump + a single i.m. dose of MTX 1 mg/kg | NA |

| - | - | 21 | G1, P0 | Tonsillectomy, laparoscopic right salpingectomy for right paratubal cyst torsion | Spontaneous | 7+3 d | Laparoscopic excision of right tubal stump after tube expression + a single i.m. dose of MTX 1 mg/kg | 100 mL |

| 38 | G4, P1 | Laparoscopic right salpingotomy for ectopic pregnancy, laparoscopic right salpingectomy for another extrauterine pregnancy | Spontaneous | 5 | Laparoscopic excision of right tubal stump+ a single i.m. dose of MTX 1 mg/kg | 600 mL | ||

| 35 | G6, P1 | Laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy for 3 ectopic pregnancies | IVF-ET | 6 | Laparoscopic bilateral excision of tubal stumps | 600 mL | ||

| Oral [21] | 2014 | 27 | G0, P0 | bilateral salpingectomy and hysteroscopic septum resection (bilateral hydrosalpinx + uterine septum), laparoscopic left cornual resection for cornual pregnancy | IVF-ET (heterotopic pregnancy) | NA | Laparoscopic excision of right tubal stump | Extensive hemo-peritoneum |

| Abraham [22] | 2015 | 27 | G5, P1 | Laparoscopic right salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy | Spontaneous | 5+6 d | Laparoscopic excision of right tubal stump | 1500 mL |

| Nishida [23] | 2015 | 26 | G4, P1 | Laparoscopic right salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy | Spontaneous | 6 | Laparoscopic excision of right tubal stump | NA |

| Xu [24] | 2016 | 28 | G0, P0 | Bilateral tubal ligation | IVF-ET | 8+6 d | Emergency laparotomic left salpingectomy/adhesion decomposition and left ovary repair |

500 mL |

| Iwahashi [25] | 2017 | 26 | G3, P0 | right partial salpingectomy + right remnant salpingectomy | Spontaneous | 6+5 d | Emergency laparotomic left salpingectomy | Massive hemo-peritoneum |

Table 1: Review of literature: interstitial pregnancies in tubal stump.

| Author | Year | Age | Gravity and parity | Previous operation history | Type of fecundation | Site of ectopic pregnancy | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferland [26] | 1991 | 32 | G4, P0 | right salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy | IVF-ET | upper retroperitoneum | LPTM |

| Fisch [27] | 1996 | 38 | G2, P0 | LPS (bilateral salpingectomy for two tubal pregnancies) | IVF-ET | abdomen (posterior aspect of the right broad ligament) | LPTM |

| - | - | 28 | G0 | LPS (bilateral salpingectomy for hydrosalpinx) | IVF-ET | right uterine cornu | LPTM |

| 33 | G1, P0 | right salpingectomy for hydrosalpinx, right tuboplasty, successively left salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy) | IVF-ET | left uterine cornu | LPTM | ||

| 32 | G0 | bilateral tuboplasty for tubal disease | IVF-ET | right uterine cornu | LPTM | ||

| Dmowsky [28] | 2002 | 34 | G0 | LPS (bilateral salpingectomy for hydrosalpinx) | IVF-ET | head of pancreas | LPTM |

| Cormio [29] | 2003 | 30 | G2, P0 | LPS (bilateral salpingectomy for two tubal pregnancies) | IVF-ET | abdomen (lower end of the omentum, adherent to the uterine fundus and cecum) | LPTM |

| Hsu [30] | 2005 | 29 | G0 | LPS (bilateral salpingectomy for hydrosalpinx) | IVF-ET | ovary | MTX and LPS |

| Cruciani [31] | 2011 | 26 | G0 | LPS (bilateral salpingectomy for hydrosalpinx) | IVF-ET | ovary | LPS |

| Xu [24] | 2016 | 28 | G3, P0 | LPS (right salpingectomy for 2 ectopic pregnancies+left salpingectomy for hydrosalpinx) | IVF-ET (heterotopic pregnancy) | Ovary | LPTM |

Table 2: Review of literature: EP in unusual sites in women with previous salpingectomies.

Case Presentation

Case 1

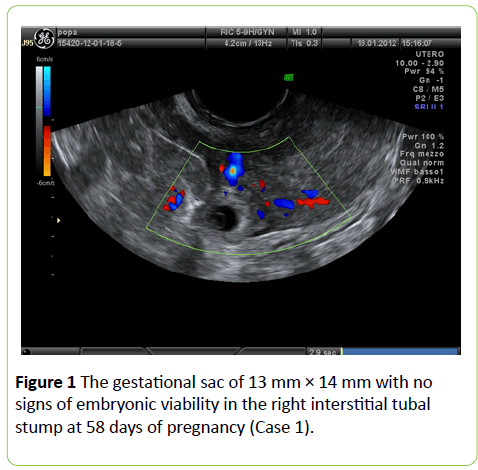

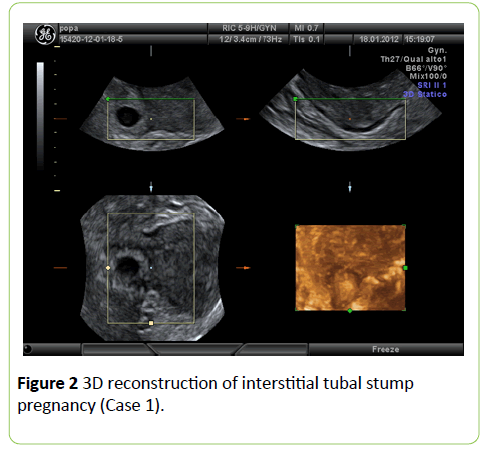

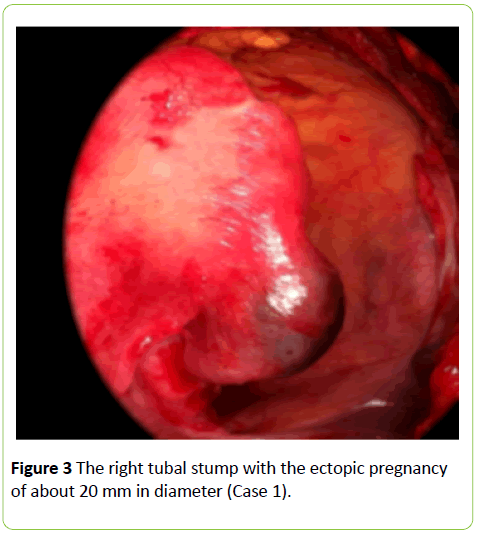

A 36-year-old patient, gravida-1 para-0, referred to our Reproductive Medical Center to ascertain implantation after IVF-ET at the 58th gestational day. The patient had a history of right laparoscopically-assisted salpingectomy for EP. Free beta- HCG was 2293 IU/L. Obstetrical examination showed a normalsize uterus with no spontaneous or evoked pain. Ultrasound transvaginal examination revealed an empty uterus and the presence of a gestational sac of 14 mm adjacent to the right uterine cornu, with no signs of viability. Power and color Doppler revealed the presence of the vascular ring with a strong peri-trophoblastic vascular activity (Figures 1-3). After careful counseling, medical management was decided upon, in accordance with the patient’s desire, using the single dose i.m. MTX regimen (50 mg/m2). Four days after treatment the patient complained sudden lower abdominal pain and weakness, that were associated with low blood pressure and severe anemia (Hb 8 g/dL). An operative laparoscopy was performed with excision of the right tubal stump. Histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of ectopic interstitial pregnancy of the right tubal stump. Intraperitoneal blood collected was around 700 mL. The patient was discharged on day 2 postoperatively and no short or long-term complications were reported.

Case 2

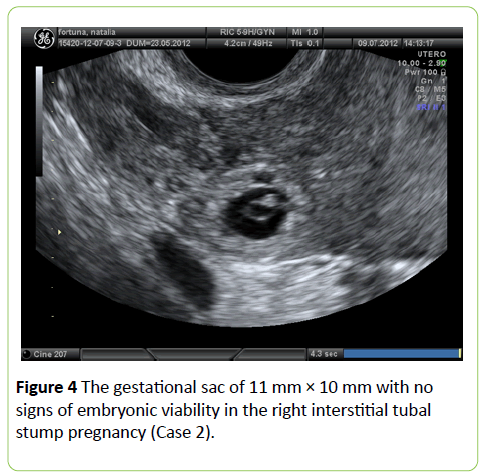

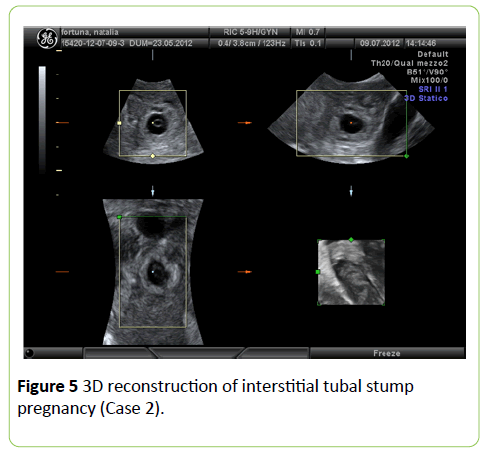

A 25-year-old patient referred to our Gynecological and Obstetric Emergency Department for acute and sudden pain arisen in the past few hours and localized in the right iliac fossa. Her past medical and surgical history was not significant except for a laparoscopic monolateral right salpingectomy for EP. She was at her 7th weeks of gestation after an embryotransfer achieved by ICSI. Pelvic examination revealed pain and tenderness in the right adnexal area and transvaginal US examination showed a gestational sac of 11 mm × 10 mm without signs of embryonic viability in the right interstitial tubal residual stump (Figures 4 and 5) with a moderate hemoperitoneum. Free beta-HCG was 8839 IU/L. The patient was then subjected to an emergency laparoscopy and the right tubal stump removal was performed. Intra-abdominal blood collected was no more than 150 mL. Histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of an ectopic interstitial pregnancy in the right tubal stump. The patient was discharged on day 2 postoperatively and no short or long-term complications were reported.

Emphysematous cholecystitis is rare clinical sequelae of acute cholecystitis. A high mortality (15%) was documented in cases of emphysematous cholecystitis [1]. Although computed tomography is the imaging diagnosis of choice, ultrasound is almost always the first initial test ordered. Sonographic finding, highly suggestive of emphysematous cholecysitis, is known as the effervescent gallbladder in which multiple echogenic foci rising from the bottom to the top within the gallbladder resembling champagne gas bubbles [2].

However, a high clinical index of suspicion of emphysematous cholecystitis should be raised in an appropriate clinical setting if the ultrasound reported “nonvisualization” or “obscured” gallbladder because the entire gallbladder wall could be filled with gas, obscuring visualization of the gallbladder. In the present case, we highlight this important sonographic finding which should be regarded as one of the ultrasound spectrums of emphysematous cholecystitis.

Discussion

Though the etiology of EP is multifactorial, as many as 50% of women with an EP have no identifiable risks. Widely accepted risk factors for EP are not independent of one another and include prior EP, prior tubal and generally pelvic surgery, IUD and a history of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) [32]. Particularly, for cases of ectopic tubal stump pregnancies, even when the visible tube portion is removed, the uterine wall still contains the interstitial fallopian portion that can host an interstitial tubal pregnancy [33]. In addition, the interstitial region receives a very significant blood supply from the uterine and ovarian arteries branches. An HP after salpingectomy can be as much threatening as EP, because the tubal interstitium rupture may lead to a sudden and excessive blood loss, worsened also by hypervascularity due to the intrauterine pregnancy [34].

In patients undergoing ART, the chances of an embryo spontaneously implanting at the interstitial tubal segment are higher when compared to a spontaneous pregnancy. Tubal stump pregnancies can occur when the embryo or the oocyte migrate through the uterine cavity or when the oocyte passes through a tubal fistula [35]. A review of the literature conducted by Chin et al. [34] reported 22 cases of cornual pregnancies after IVF-ET.

In women with a history of salpingectomy, some cases of unusual implantation sites have been reported. Fisch et al. [27] in 1996 reported a case of an abdominal pregnancy following in vitro fertilization in a woman subjected to bilateral salpingectomy. Dmowski et al. [28] reported a retroperitoneal ectopic pregnancy located in the head of the pancreas in a similar patient. Ferland et al. [26] reported a retroperitoneal pregnancy in a patient with previous right salpingectomy secondary to an ectopic gestation. Agarwal et al. [36] studied 26 ectopic pregnancies detected after embryo-transfer during a 7-year period and seven of these were located in the cornual or tubal stump after prior salpingectomy. Four out of seven women were treated with MTX, but in only one case conservative treatment was successful. The other three cases were tubal implantations, with one rupture during the treatment. Chang et al. [37] presented a case of bilateral simultaneous tubal sextuplets pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization–embryo transfer following salpingectomy. Chen et al. [38] described three cases of cornual pregnancies occurring after IVF-ET. Two of these patients had prior bilateral salpingectomy, whereas another had prior tuboplasty for tubal disease. Nabeshima et al. [39] presented the case of a 38-yearold woman, with a history of left salpingectomy from an ectopic pregnancy, admitted for treatment of another presumed ectopic pregnancy. Surgery was performed for a suspected left cornual pregnancy and with laparoscopy the gestational sac was removed; the uterus was preserved.

An accurate diagnosis should lead to a proper treatment of the patient: two different schemes were proposed. Lau and Tulandi listed three main sonographic criteria to appropriately identify interstitial and tubal stump pregnancies: an empty uterus; a gestational sac viewed >10 mm from the most lateral edge of the uterine cavity; a slight myometrial thickness around the gestational sac Diagnostic specificity was 88% to 93% but sensitivity was 40% [40]. Timor-Tritsch et al’s study proposed supposedly a more effective identification system: the finding of an “interstitial line sign” representing an iperechoic line from the adjacent interstitial ectopic mass of the tubal mid-portion that can represent the tubal lesion or the endometrial canal. Diagnostic specificity was 98% and sensitivity was 80% [41].

Unilateral and even bilateral salpingectomy cannot prevent subsequent ectopic (and heterotopic) pregnancies. Even more catastrophic conditions may occur because the ectopic gestation is always located within the interstitial tubal portion, rather than in the ampullary portion of the fallopian tube.

The uterine corn has an abundant blood supply from branches of the ovarian and uterine arteries and a ruptured cornu can have tragic consequences from sudden and excessive blood loss. For this reason, these pregnancies are generally associated with very high serum hCG levels and the mortality rates for interstitial pregnancy accounts for 20% of all EP [42].

At the beginning, the traditional treatment for interstitial pregnancy was cornual resection by laparotomy or hysterectomy. In the last decades operative laparoscopy has generally been considered the “gold standard” for the treatment of tubal ectopic pregnancies, but medical treatment is viewed with increasing interest. The medical treatment of the patient is an option that can be followed but with scarce success. The estimated success rate for medical treatment with methotrexate of interstitial pregnancy is lower than that for treatment of ectopic pregnancies located in the tubal ampulla or isthmus. Although medical therapy can be successful at serum hCG concentrations considerably higher than 3000 IU/l, quality-of-life data suggest that methotrexate is only an attractive option for women with an hCG below 3000 IU/l [43]. Reviewing the literature, we found only one case of tubal stump pregnancy treated successfully with a single i.m. dose of MTX (100 mg) with a serum HCG concentration of 12.470 IU/ml [44].

The presence of cardiac activity in an ectopic pregnancy is associated with a reduced chance of success following medical therapy and should be considered a contraindication to medical treatment and a similar behavior should be considered for EP of the tubal stump.

Conclusion

In conclusion, early transvaginal ultrasound should be considered in women with a history of salpingectomy in order to allow a prompt diagnosis of tubal stump EP. Physicians should bear in mind this severe and emergency obstetrical condition when treating tubal diseases such as PID and EP, whereupon a complete removal of the Fallopian tube should be mandatory.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The Institutional Review Board approved this study protocol.

Authors' contributions

RL contributed to the concept and design of the case report. DC and SD analyzed and interpreted the patient data. CJ and ML gave a major contribution in writing the manuscript; MM and FV contributed in collecting and interpreting the data. AC and PMG contributed critically reviewing the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Ko PC, Liang CC, Lo TS, Huang HY (2011) Six cases of tubal stump pregnancy: complication of assisted reproductive technology? Fertil Steril 95: 2432.

- Perkins KM, Boulet SL, Kissin DM, Jamieson DJ (2015) Risk of ectopic pregnancy associated with assisted reproductive technology in the United States, 2001–2011. Obstet Gynecol 125: 70-78.

- Farquhar CM (2005) Ectopic pregnancy. Lancet 366: 583-591.

- Smith LP, Oskowitz SP, Dodge LE, Hacker MR (2013) Risk of ectopic pregnancy following day-5 embryo transfer compared with day-3 transfer. Reprod Biomed Online 27:407-413.

- Takeda A, Hayashi S, Imoto S, Sugiyama C, Nakamura H (2014) Pregnancy outcomes after emergent laparoscopic surgery for acute adnexal disorders at less than 10 weeks of gestation. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 40: 1281-1287.

- Talbot K, Simpson R, Price N, Jackson SR (2011) Heterotopic pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol 31: 7-12.

- Barrenetxea G, Barinaga-Rementeria L, Lopez de Larruzea A, Agirregoikoa JA, Mandiola M, et al. (2007) Heterotopic pregnancy: Two cases and a comparative review. Fertil Steril 87: 417.e9–417.

- Felekis T, Akrivis C, Tsirkas P, Korkontzelos I (2014) Heterotopic triplet pregnancy after in vitro fertilization with favorable outcome of the intrauterine twin pregnancy subsequent to surgical treatment of the tubal pregnancy. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2014: 356131.

- Corti A, Rolandi L (1964) Ectopic pregnancy in the site of prior adnexectomy. Osp Maggiore 59: 413-422.

- Benzi G, Mazza L (1967) Recurrence of ectopic pregnancy in a residual tubal stump after prior adnexectomy for extra-uterine pregnancy. Minerva Ginecol 19: 171-178

- Krzaniak S (1968) Ectopic gestation in a tubal stump. Postgrad Med J 44: 191-192.

- Bernardini L, Valenzano M, Foglia G (1998) Spontaneous interstitial pregnancy on a tubal stump after unilateral adenectomy followed by transvaginal colour doppler ultrasound. Hum Reprod 13: 1723-1726.

- Sills ES, Perloe M, Kaplan CR, Sweitzer CL, Morton PC, et al. (2002) Uncomplicated pregnancy and normal singleton delivery after surgical excision of heterotopic (cornual) pregnancy following in vitro fertilization/embryo transfer. Arch Gynecol Obstet 266: 181-184.

- Milingos DS, Black M, Bain C (2008) Three surgically managed ipsilateral spontaneous ectopic pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 112: 458-459.

- Faleyimu BL, Igberase GO, Momoh MO (2008) Ipsilateral ectopic pregnancy occurring in the stump of a previous ectopic site: A case report. Cases J 1: 343.

- Muppala H, Davies J (2009) Spontaneous proximal tubal stump pregnancy following partial salpingectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol 29: 69-70.

- Pluchino N, Ninni F, Angioni S, Carmignani A, Genazzani AR, et al. (2009) Spontaneous cornual pregnancy after homolateral salpingectomy for an earlier tubal pregnancy: A case report and literature review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 16: 208-211.

- Sturlese E, Retto G, Palmara V, De Dominici R, Lo Re C, et al. (2009) Ectopic pregnancy in tubal remnant stump after ipsilateral adnexectomy for cystic teratoma. Arch Gynecol Obstet 280: 1015-1017.

- Shavit T, Paz-Shalom E, Lachman E, Fainaru O, Ellenbogen A (2013) Unusual case of recurrent heterotopic pregnancy after bilateral salpingectomy and literature review. Reprod Biomed Online 26: 59-61.

- Drakopoulos P, Julen O, Petignat P, Dällenbach P (2014) Spontaneous ectopic tubal pregnancy after laparoscopic tubal sterilisation by segmental isthmic partial salpingectomy. BMJ Case Rep 22.

- Oral S, Akpak YK, Karaca N, Babacan A, Savan K (2014) Cornual heterotopic pregnancy after bilateral salpingectomy and uterine septum resection resulting in term delivery of a healthy infant. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2014: 157030.

- Abraham C, Seethappan V (2015) Spontaneous live recurrent ectopic pregnancy after ipsilateral partial salpingectomy leading to tubal rupture. Int J Surg Case Rep 7C: 75-78.

- Nishida M, Miyamoto Y, Kawano Y, Takebayashi K, Narahara H (2015) A case of successful laparoscopic surgery for tubal stump pregnancy after tubectomy. Clin Med Insights Case Rep 8: 1-4.

- Xu Y, Lu Y, Chen H, Li D, Zhang J, et al. (2016) Heterotopic pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer after bilateral total salpingectomy/tubal ligation: Case report and literature review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 23: 338-345.

- Iwahashi N, Deguchi Y, Horiuchi Y, Ino K, Furukawa K (2017) A third surgically managed ectopic pregnancy after two salpingectomies involving the opposite tube. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 1653529.

- Ferland RJ, Chadwick DA, O'Brien JA, Granai CO 3rd (1991) An ectopic pregnancy in the upper retroperitoneum following in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Obstet Gynecol 78: 544-546.

- Fisch B, Peled Y, Kaplan B, Zehavi S, Neri A (1996) Abdominal pregnancy following in vitro fertilization in a patient with previous bilateral salpingectomy. Obstet Gynecol 88: 642-643.

- Dmowski WP, Rana N, Ding J, Wu WT (2002) Retroperitoneal subpancreatic ectopic pregnancy following in vitro fertilization in a patient with previous bilateral salpingectomy: How did it get there? J Assist Reprod Genet 19: 90-93.

- Cormio G, Santamato S, Putignano G, Bettocchi S, Pascazio F (2003) Concomitant abdominal and intrauterine pregnancy after in vitro fertilization in a woman with bilateral salpingectomy. A case report. J Reprod Med 48: 747-749.

- Hsu CC, Yang TT, Hsu CT (2005) Ovarian pregnancy resulting from cornual fistulae in a woman who had undergone bilateral salpingectomy. Fertil Steril 83: 205-207.

- Cruciani L, Gerli S, Baiocchi G, Clerici G, Antonelli C, et al. (2011) Ovarian pregnancy after in vitro fertilisation in a woman with previous bilateral salpingectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol 31: 270-271.

- Marion LL, Meeks GR (2012) Ectopic pregnancy: History, incidence, epidemiology, and risk factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol 55: 376-386.

- Herman A, Ron-el R, Golan A, Soffer Y, Bukovsky I, et al. (1991) The dilemma of the optimal surgical procedure in ectopic pregnancies occurring in in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod 6: 1167-1169.

- Chin HY, Chen FP, Wang CJ, Shui LT, Liu YH, et al. (2004) Heterotopic pregnancy after in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 8: 411-416.

- Bu Z, Xiong Y, Wang K, Sun Y (2016) Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy in assisted reproductive technology: A 6-year, single-center study. Fertil Steril 106: 90-94.

- Agarwal SK, Wisot AL, Garzo G, Meldrum DR (1996) Cornual pregnancies in patients with prior salpingectomy undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Fertil Steril 65: 659-660.

- Chang CC, Wu TH, Tsai HD, Lo HY (1998) Bilateral simultaneous tubal sextuplets: Pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization--embryo transfer following salpingectomy. Hum Reprod 13: 762-765.

- Chen CD, Chen SU, Chao KH, Wu MY, Ho HN, et al. (1998) Cornual pregnancy after IVF-ET. A report of three cases. J Reprod Med 43: 393-396.

- Nabeshima H, Nishimoto M, Utsunomiya H, Arai M, Ugajin T, et al. (2010) Total laparoscopic conservative surgery for an intramural ectopic pregnancy. Diagn Ther Endosc 504062.

- Lau S, Tulandi T (1999) Conservative medical and surgical management of interstitial ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril 72: 207-215.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Matera C, Veit CR (1992) Sonographic evolution of cornual pregnancies treated without surgery. Obstet Gynecol 79: 1044-1049.

- Shen L, Fu J, Huang W, Zhu H, Wang Q, et al. (2014) Interventions for non-tubal ectopic pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 7: CD011174.

- Barnhart K, Spandorfer S, Coutifaris C (1997) Medical treatment of interstitial pregnancy: A report of three unsuccessful cases. J Reprod Med 42: 521-524.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists RCOG Guideline No. 21. (2004) The management of tubal pregnancy. England.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences